Here are a collection of news items that I didn’t get a chance to write posts about this week:

Ukrainian woman whose rape caused protests dies

An 18-year-old Ukrainian woman who prosecutors say was gang-raped, half-strangled and then set on fire in an attack that sparked street protests in a provincial Ukrainian town, has died, a hospital official said on Thursday. Hundreds of people took to the streets earlier this month after police released two of Oksana Makar’s three suspected attackers whose parents had political connections, re-igniting a public debate on corruption in the ex-Soviet republic. Interior Minister Vitaly Zakharchenko confirmed earlier this month that the parents of at least one of the three suspects were former government officials in the Mykolaiv region.

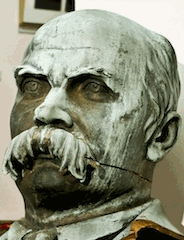

What Goes on in There?: Taras H. Shevchenko Museum

the two-storey building that houses Toronto’s

Taras H. Shevchenko Museum is a cultural oasis, wedged incongruously between a dentist’s office and an employment agency. Inside, visitors will find a two-storey homage to Shevchenko, a 19th-century Ukrainian poet, artist, and rebel. The museum’s original location north of Oakville was damaged by arson in 1988. In 2001, its three-metre bronze statue of Shevchenko was sawed down and stolen by hooligans. Only the head was returned, when a Hamilton antique dealer tried to sell it back to the museum last November, apparently unaware of its criminal origins

Child coal mining film banned at Kyiv festival

After scooping 10 awards at international festivals, a Ukrainian-Estonian documentary on child labor in abandoned mines finally made it home to Ukraine. It was scheduled to premiere at an international documentary festival on March 24. But instead, in a bizarre and unprecedented turn of events, “Pit Number 8†was banned by its own Ukrainian producer.

I actually had the opportunity to see the film last year at HotDocs, and it shows the grim life of people who work the dangerous coal mines – the heart of Yanukovych’s fan base. The entire movie is up on YouTube.

The Economist has the worst style guide when it comes to Ukraine

Style guides are used by newspapers to ensure the same guidelines are used by multiple journalists referring to the same thing, but I was completely shocked by what they have in their entry for Ukrainian names:

Since Ukrainian has no g, use h: Hryhory, Heorhy, Ihor (not Grigory, Georgy, Igor). Exception: Georgy Gongadze.

There very much exists ‘g’ in Ukrainian, it’s ґ, and ‘h’ is г. Conversely in Russian there is no ‘h’, just ‘g’ which is г . So a Ukrainian ‘h’ is a Russian ‘g’ which is why sometimes you’ll see golubtsi instead of holubtsi, and Golodomor instead of Holodomor.

Use the familiar British renderings of placenames: Chernigov not Chernihiv, Kiev not Kyiv, Lvov not Lviv, and Odessa not Odesa.

Those Soviet spellings went out decades ago. The Economist likes to think if you disagree then ‘it’s time to get a life’.

Anti-advertising for Euro 2012: We’re going to Ukraine

“Are you finally taking me to Paris?” “Better… we’re going to Ukraine!”

Easter

It’s April 8th 2012 for the Gregorian Calendar (ie. the Western world). For the rest of us who follow the Julian Calendar it’s April 15th.

Inside Ukrainian Dance

A local author takes us behind the colourful curtain of Ukrainian Dance. In his book, Dr. Andriy Nahachewsky explores the differences between what the audience sees on stage…and what would happen in a small Ukrainian village.

Baba’s medicine

We’re stepping back in time for some medical remedies Baba used in her kitchen. It’s all in a new book by a local author.

An odd, bitter piece was

An odd, bitter piece was